Satellites that will form part of SpaceX's Starlink constellation are waiting to be launched into orbit from a Falcon 9 rocket on May 24. Photo: SpaceX.

When Russian forces entered Ukraine in early 2022, one of Kiev's first moves was to send a post to billionaire Elon Musk on X: Ukraine needs satellite internet.

In just a few days, thousands of Starlink terminals arrived, restoring command and control on the battlefield, despite intense jamming efforts from Russia.

Moscow initially tried to jam the signals – with some success, it was said. But as SpaceX quietly updated its software and reconfigured its satellite constellation, many of the Russian jammers went silent. The tide of battle turned.

The incident caused a stir in military circles around the world – especially in Beijing.

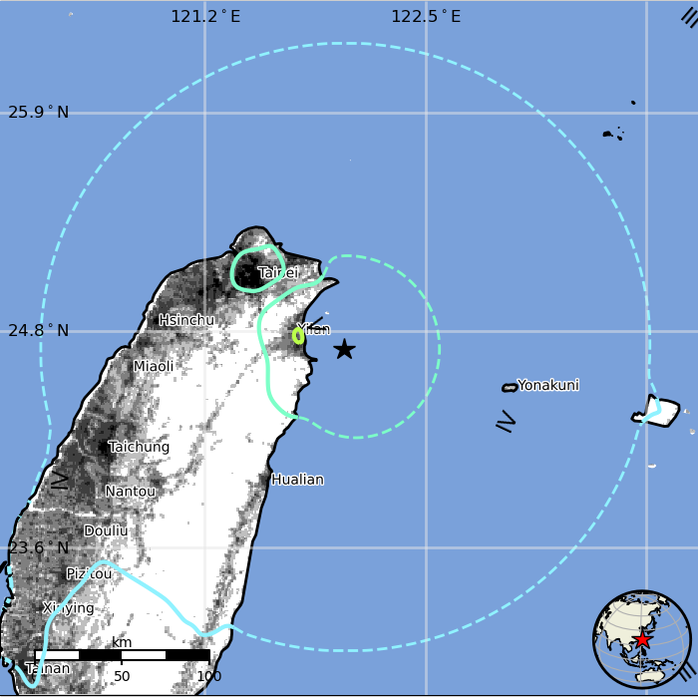

For the People's Liberation Army (PLA), preparing for a potential campaign involving Taiwan means answering a pressing question: how to gain electromagnetic superiority when an adversary has access to a satellite constellation of more than 10,000 devices, capable of frequency hopping, self-tuning, and real-time anti-jamming?

A groundbreaking simulation study by Chinese scientists has provided the most detailed public analysis to date of how the PLA might attempt to disrupt one of the most fortified communications systems ever built.

The study, published on November 5 in the Chinese peer-reviewed scientific journal Systems Engineering and Electronics, found that jamming Starlink over an area the size of Taiwan is technically feasible, but only if deployed on a massive scale, requiring 1,000 to 2,000 electronic warfare drones.

The paper, titled “Simulation Study of Distributed Jamming Devices Against Downlink Communication Transmission of Ultra-Large Satellite Constellation,” was conducted by a research team from Zhejiang University and the Beijing Institute of Technology (BIT) – a leading unit in Chinese defense research.

“Starlink’s orbital planes are not fixed, and the orbital motion of the satellite constellation is complex, and the number of satellites entering the observation area is constantly changing,” the team led by defense researcher Yang Zhuo wrote. “This space-time uncertainty poses a great challenge to any third party attempting to monitor or disable the Starlink satellite constellation.”

Normally, satellite communications rely on a few large geostationary satellites fixed over the equator. To disable them, the Chinese military would simply overwhelm the signals from the ground.

But Starlink is different. Its satellites are low, fast-moving, and massive. A terminal doesn’t connect to a single satellite—it constantly hops between multiple devices, forming a mesh network across the sky. Even if you jam one signal, the connection will jump to another satellite in seconds, according to researchers.

Additionally, Starlink uses advanced phased array antennas and real-time frequency hopping techniques, largely controlled remotely by SpaceX engineers in the US.

According to Mr. Yang’s team, Starlink can only be countered by a distributed jamming strategy. Instead of relying on a few high-powered ground stations, hundreds or thousands of small, synchronized jammers would have to be deployed in the sky—mounted on UAVs, balloons, or planes—to form an “electromagnetic shield” over the battlefield.

Using real Starlink satellite data, the team simulated the dynamic positions of the satellites over 12 hours over eastern China.

They simulated the downlink signal strength of Starlink satellites, the reception pattern of terminals, the propagation of interference from the ground to the sky and vice versa, as well as the resonance effect of multiple jammers impacting the same terminal from multiple angles.

They then deployed a virtual grid of jammers flying at an altitude of 20 kilometers, spaced 5 to 9 kilometers apart like a chessboard in the sky.

An antenna of the Starlink satellite broadband system funded by US tech billionaire Elon Musk in Izyum, Kharkiv region, Ukraine in September 2022. Photo: AFP.

Each device emits jamming at different power levels, simulating real-world electronic warfare payloads.

Two types of antennas were tested – a wide beam, which provides greater coverage but disperses energy; and a narrow beam, which is more powerful but requires high precision.

The simulation calculates at every point on the ground whether the Starlink terminal still maintains a usable signal.

Under optimal conditions – using a powerful and expensive 26 dBW (400 watt) jammer, a narrow beam antenna, and a distance of 7km – each jammer can disable Starlink over an average range of 38.5 km².

Taiwan is about 36,000 square kilometers. Covering the island with a stable jamming zone would require at least 935 coordinated devices, not counting redundancies for broken devices, signal-blocking mountains, and the possibility of Starlink upgrading its anti-jamming capabilities in the future.

Using a 23 dBW weaker power source and a 5km distance would double the number of devices to about 2,000.

Mr. Yang's team said the results are still preliminary because Starlink keeps many core technologies secret.

“If in the future it is possible to collect real measurement data on the radiation pattern of Starlink terminals, as well as experimental values of the interference rejection coefficient, the assessment results will be more accurate,” they said.